Risken för MIS-C – som är vanligast i gruppen 5-11 år efter COVID-19 – tycks minska efter vaccinering bland tonåringar. Data för de i åldern 12-18 visar att de får gott skydd mot sjukhuskrävande COVID-19 av vaccinen. Därtill tyder data efter fler än 8 miljoner givna doser, på låg risk för allvarliga biverkningar och myokardit av vaccinen, bland de i åldern 5-11 år.

Efter en kort sammanfattning följer respektive punkt (första på svenska, de senare på engelska)

- Data publicerad i JAMA samt i CDC:s tidskrift tyder på påtagligt sänkt risk för MIS-C bland tonåringar (ålder >12) som har vaccinerats för COVID-19 i Frankrike (punkt 1-2), och en ny CDC-rapport med amerikansk data visar att enbart 0.4% av sjukhusvårdade ungdomar var fullvaccinerade, och enbart 4.4% var partiellt vaccinerade (punkt 3).

- Enligt preliminära data för upp till 8.7 miljoner vaccinmottagare i USA, med nästan upp till nära 2 månaders observation sen åtminstone första dosen, har därtill mycket få allvarliga biverkningar inträffat. På samma sätt tycks mycket få vaccinerade barn i denna ålder ha fått myokardit (totalt 11 fall), efter att dos 1 och 2 givits (punkt 4).

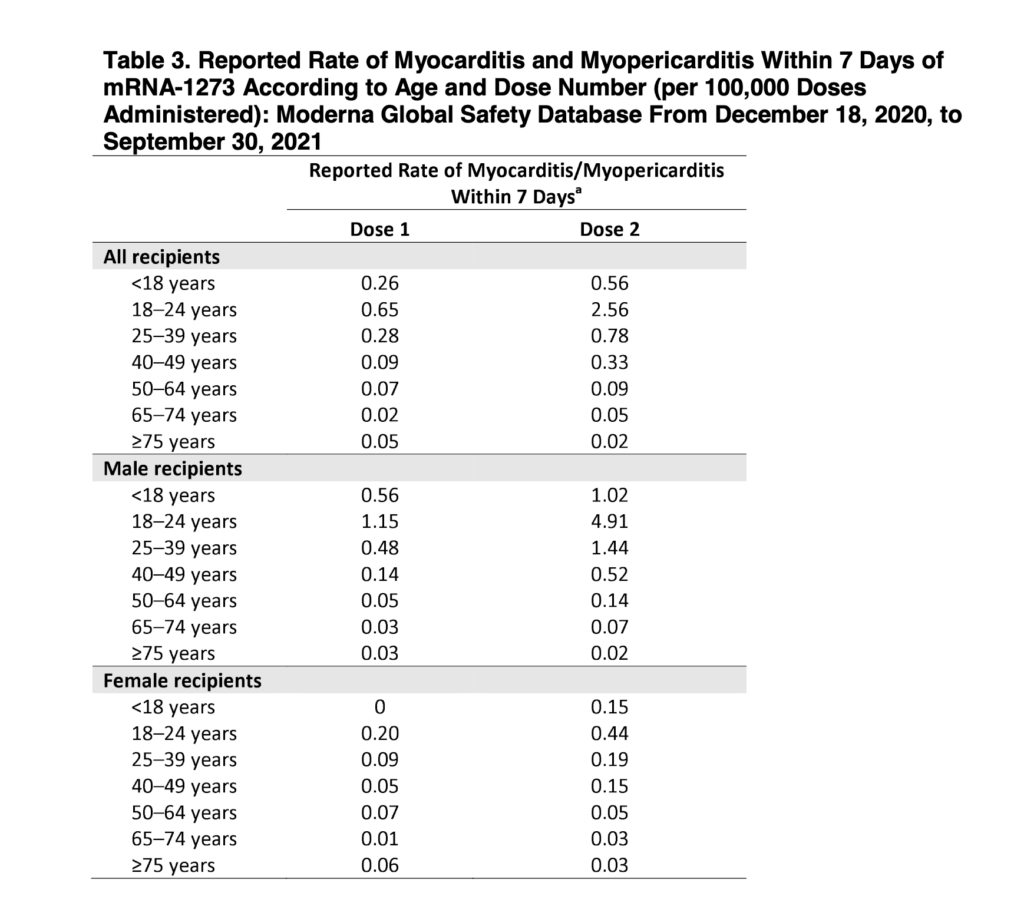

- Samtidigt styrker än mer data (bland 38 miljoner vaccinmottagare), publicerad i Nature Medicine, att bland de över åldern 16 år, var myokarditrisken i stort sett enbart förhöjd hos de under 40 år. Sammantaget är dock riskerna för myokardit högre efter infektion med SARS-CoV-2, en infektion som också avsevärt sågs öka risken för t.ex. arrytmi (>5x ökning över baseline), samt för sjukhuskrävande eller dödlig perikardit (~3.8-4-9 gånger) (se denna tråd och mitt förra inlägg för fler detaljer).

- Samtidigt styrker än mer data (bland 38 miljoner vaccinmottagare), publicerad i Nature Medicine, att bland de över åldern 16 år, var myokarditrisken i stort sett enbart förhöjd hos de under 40 år. Sammantaget är dock riskerna för myokardit högre efter infektion med SARS-CoV-2, en infektion som också avsevärt sågs öka risken för t.ex. arrytmi (>5x ökning över baseline), samt för sjukhuskrävande eller dödlig perikardit (~3.8-4-9 gånger) (se denna tråd och mitt förra inlägg för fler detaljer).

- Avslutningsvis tyder en ny amerikansk studie på att risken för diabetes är förhöjd efter COVID-19 hos barn under 18 års ålder (punkt 5). Riskförhöjningen varierade något men sågs även jämfört med andra akuta luftvägsinfektioner (prepandemiska). Dock saknades en del variabler såsom viktstatus, som är viktiga för att närmare förstå orsakssambanden. Här finns ännu ingen data på hur denna risk påverkas vid vaccinering, men (liksom för MIS-C) tyder samtidigt annan preliminär data på att vaccinering – särskilt med två doser – minskar risken för många komplikationer som kan uppstå till följd av COVID-19

1. Vaccinering minskar risken för COVID-19-komplikationen MIS-C hos tonåringar

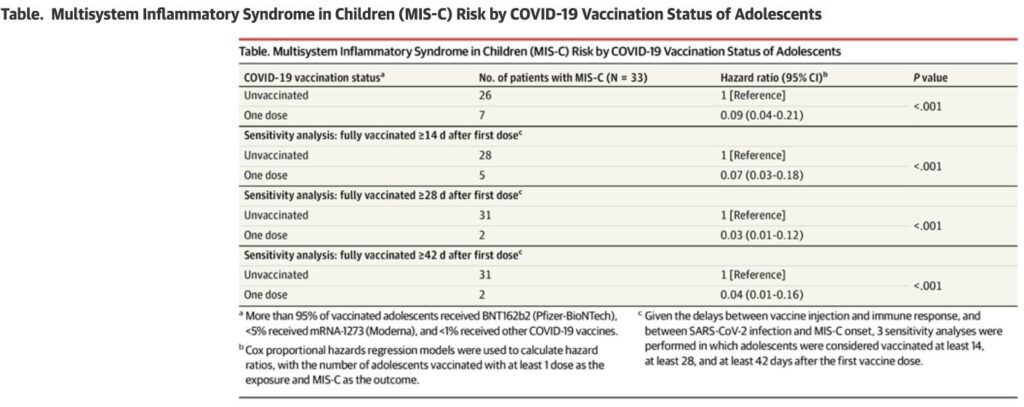

I den första analysen i tidskriften JAMA (20/12) av Levy et al., undersöktes risken för MIS-C (multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children) bland bland tonåringar i Frankrike under perioden september-oktober 2021. MIS-C är en komplikation som i mer ovanliga fall kan uppstå några veckor efter en infektion med SARS-CoV-2.

Alla i åldern 12-18 med MIS-C som under perioden lades in på en av deras barnintensiver (PICUs) ingick i studien. De utförde även så kallade sensitivitetsanalyser för att beakta eventuella fördröjd vaccineffekt på upp till 42 dagar efter dos 1 (dvs. upp till 2 veckor efter dos 2).

Den 31:a oktober hade 76.7% av Frankrikes 5 miljoner (4.99 M) tonåringar vaccinerats med minst en dos; 72.8% var fullvaccinerade (>95% Pfizer). Under perioden 1:a september till 31:a oktober drabbades 107 barn av MIS-C – av dessa var 33 i den åldern att de hade kunnat vaccineras (medelålder 13.7; 81% män; 88% PICU-vårdade). Inga av dessa individer var fullvaccinerade, 7 hade fått en dos (~25 dagar tidigare) och 26 var helt ovaccinerade.

Utifrån denna data fann forskarna en betydligt lägre risk (hazard ratio, HR) för att få MIS-C efter första vaccindosen jämfört med hos ovaccinerade (HR 0.09, 95%CI 0.04-0.21; P<0.001). Räknade man ≥14 dagar efter första dosen var HR 0.07; ≥28 dagar efter dos 1 var HR 0.03; ≥42 dagar efter 1:a dosen (dvs. återigen, 2 veckor efter dos 2) var HR ännu lägre på 0.04 (överlappande konfidensintervall mellan dessa sensitivitetsanalyser; se skärmdumpen nedan).

Betydligt färre vaccinerade kontra ovaccinerade barn fick alltså MIS-C i denna analys – skyddet var som nämnt signifikant i flera analyser. De ofullständigt vaccinerade barn som ändå fick MIS-C, utvecklade diagnosen i snitt ~25 dagar efter vaccinering. Efter en infektion med SARS-CoV-2 tar det i snitt lite längre (~28-35 dagar) att utveckla MIS-C. Detta tyder det på att de som ändå var vaccinerade och fick MIS-C, inte hade hunnit utvecklat ett fullgott vaccin-medierat skydd när de fick MIS-C. Att MIS-C ej sågs hos fullvaccinerade individer kan vidare enligt författarna tala för att två doser kan ge än bättre skydd.

Tyvärr saknades möjlighet att t.ex. justera för ko-morbiditeter, etnicitet eller kön. Men resultaten stämmer mycket väl med en senare analys (se punkt 2 nedan, beskriven på engelska), som publicerats i en av CDC:s tidskrifter.

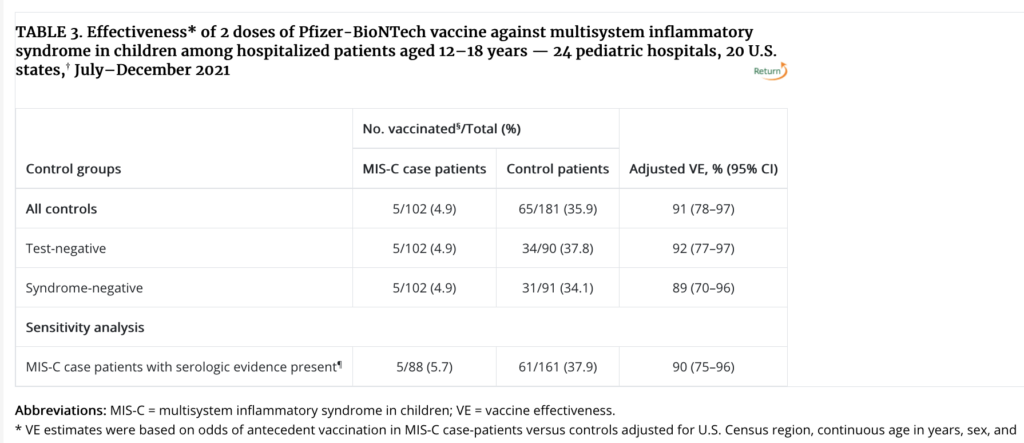

2. Another study finds that adolescents who had been fully vaccinated had a 91% risk reduction of the COVID-19 complication MIS-C

- The new test-negative case-control analysis by Zambrano et al. was based on the period July 1–December 9, 2021, and used data from 24 U.S. pediatric hospitals. They looked at adolescents age 12-18 who had been fully vaccinated (2 doses of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine).

- 283 patients were included: 102 MIS-C case-patients and 181 controls, with a median age of 14.5. Of the total group, 58% had at least one underlying condition (including obesity, 39.2% in the MIS-C group and ~69% in the control group). ~5% of case-patients and ~36% of controls were fully vaccinated against COVID-19. Furthermore, of those with MIS-C who required life support, no individual was fully vaccinated.

- They carried out several sensitivity analyses, with very similar results to the main finding, i.e. a circa 90% lower risk of MIS-C in vaccinated compared with unvaccinated individuals. These sensitivity analyses covered those who had COVID-19 symptoms but had tested negative for SARS-CoV-2 and only analysing those with positive serology (antibody evidence of a SARS-CoV-2 infection).

- Note that here (as opposed to the JAMA study above), they could not infer the degree of protection from only one vaccine dose, and did not estimate it for the period covering 0-28 days from the 2nd dose (because it takes ~2 weeks to achieve vaccine protection, and MIS-C in general develops 2-6 weeks after a SARS-CoV-2 infection). There may also be bias in the data as it looked at those who sought medical care across U.S. hospitals, and they could not examine possible effect over time (i.e. possible waning).

- These results are however very consistent with the prior study above in JAMA, from France. The screenshot below also shows the sensitivity analyses.

3. Most (99.6%) children age 12-18 who were hospitalized for COVID-19 were unvaccinated or not fully vaccinated

In this CDC MMWR report by Wanga et al., data was obtained from six U.S. hospitals in areas with a high incidence of SARS-CoV-2 during the July-Aug 2021 period (e.g. in Florida and Texas). Among 915 hospitalized patients hospitalized with a) COVID-19, b) incidental SARS-CoV-2 infection, or c) MIS-C, below age 18, most (78%) were hospitalized for COVID-19 (2.7% had MIS-C).

Among the patients hospitalized for COVID-19, 32.5% had no underlying medical conditions (the most common underlying conditions were obesity (32%) and asthma (16%)). Obesity was however far more common in the hospitalized 12-17 age group (61.4%). Among patients hospitalized for COVID-19, 29.5% were admitted to the ICU, 1.1% received ECMO, and 1.5% (11) died.

There were 272 patients hospitalized for COVID-19 who were vaccine-eligible. Only one (0.4%) of these patients was fully vaccinated. Another 12 patients (4.4%) were partially vaccinated with an mRNA COVID-19 vaccine, when they were hospitalized, and a total of 196 were known to be unvaccinated.

However, already in September we had CDC data indicating that adolescents age 12-17 were highly protected from hospitalization (10-fold lower rate) if they were vaccinated compared with if they were unvaccinated. So very similar findings to the above, new data.

4. Follow-up data indicates a low risk of side effects and myocarditis after vaccination in the 5-11 year-old group

The U.S. started vaccinations for kids age 5-11 on Nov 2, 2021, after a recommendation by e.g. the U.S: ACIP (Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices). Kids in the 5-11 year age group in the U.S., and most other places, receive Pfizer’s mRNA vaccine, but at a lower dose of only 10 µg per dose (compared with 30 µg per dose for older individuals). Already on December 17, the CDC put out a report detailing a low risk of vaccine complications and equally low rate of vaccine-associated myocarditis.

For myocarditis, in the Dec 17 report, they noted 8-14 cases out of 7 141 428 (7.1 Million) administered Pfizer mRNA COVID-19 vaccine doses, which (preliminarily) would put the rate at ~1.1-1.26 cases/Million doses. Note: There was limited second dose data at that point (5.126 M 1st doses; 2.014 M 2nd doses; data shared from the CDC Vaccine Task Force. Twitter thread format here.

A follow-up to this data was published on Dec 30, 2021 – also from the CDC. There they detailed safety data based on over 8 million administered vaccine doses to the 5-11 year age group. At the follow-up, there were a total of 11 verified cases that met the definition for myocarditis (of these 7 had recovered and 4 were still recovering). As a comparison for this data, Sweden has 620 355 children age 5-9 (I didn’t find specifics for the entire 5-11-year age range). This means that the above vaccination data covers Sweden’s entire corresponding cohort of children in this age range by several factors.

They also studied myocarditis incidence after vaccination using their VSD (Vaccine Safety Datalink) system, which links in “real-time” to health records for 12 million persons per year (of all ages). In VSD they did not note any myocarditis case among 226 000 dose 1 recipients, nor among 107 000 dose 2 recipients, in the relevant 0-7 & 0-21 day post vaccination windows.

Among VAERS reports (ie the subset of possible adverse effects) 97.6% were considered non-serious. There were 2 deaths that were still under review, but both had quite complicated medical history (e.g. hypoxic encephalopathy). Note that there are also initially some additional reports of myocarditis pending, but at the current number at 11, that equates to a rate ~1.26 cases per million administered doses, based on this data (more cases may still arise as it can e.g. take time to report, and more second doses will be administered).

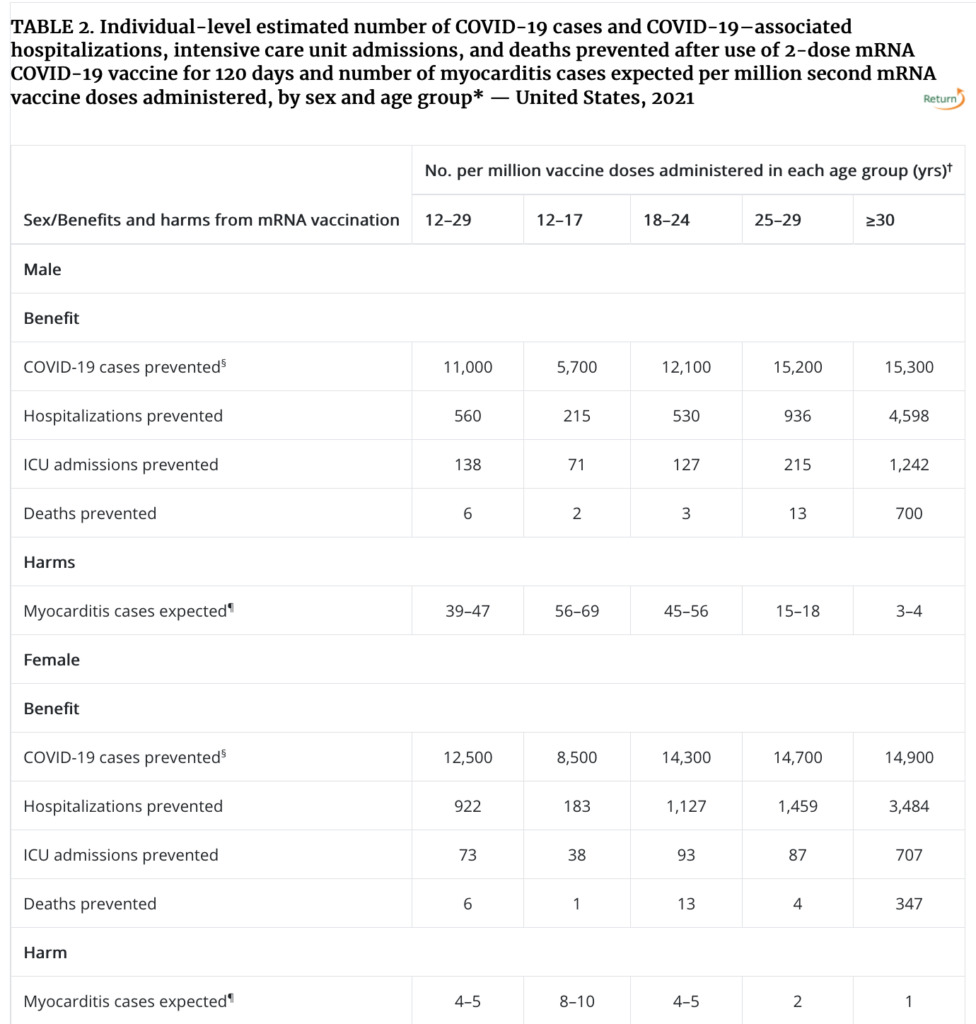

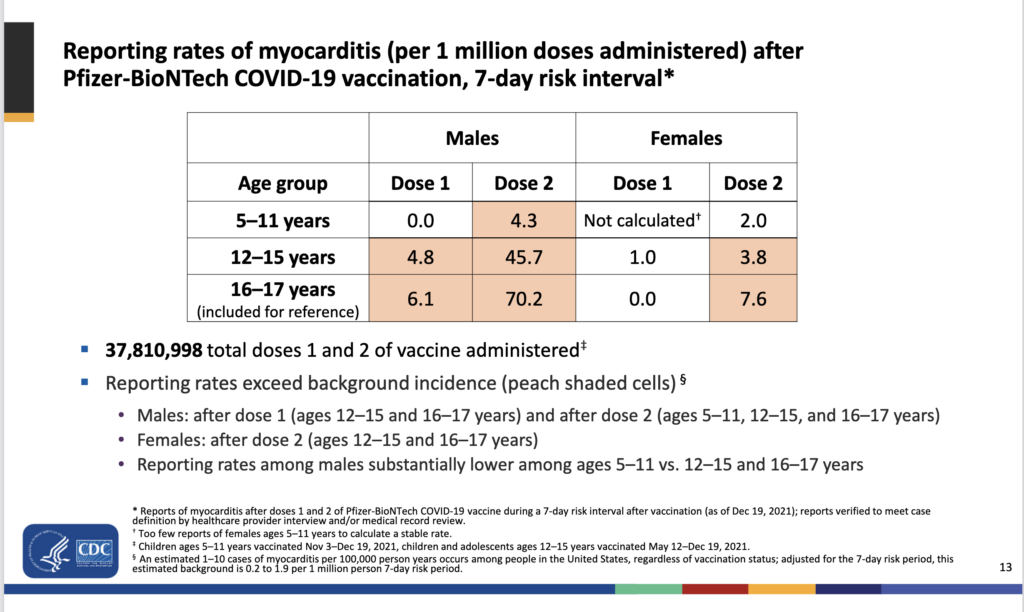

The initial data indicated that myocarditis – similar to other age groups – was more common after the second dose (6 cases among 2.014M recipients). But even so, the rate of vaccine-associated myocarditis seems to be about 10 times lower lower than what has been reported for vaccine-associated myocarditis in the adolescent (12-17) to lower 20’s age groups (see this CDC presentation for a numbers comparison, as well as the screenshot below).

The December 17 report indicated that possible complications of the vaccines were also rare (n=81 reported cases out of 7.1 Million doses reported), and some may have had other causes (etiology) as can be inferred from their slide: e.g. an elevated CRP level (light inflammation, n=10). In the follow-up Dec 30 data, there were only 100 serious events among the 8.7 million vaccine recipients, the most common being fever (29 cases), vomiting (21 cases), and increased troponin (15 cases).

The v-safe data (digital active surveillance of vaccine recipients), among 42,504 1st dose and 39,899 2nd dose recipients of age 5-11, indicated that local and systemic reactions were less frequent among those aged 5-11, compared with those aged 12-17. Hospitalizations were very uncommon (0.02% among both 1st and 2nd dose recipients).

Note that VAERS is a voluntary passive reporting system and may therefore have biases and underreporting (which may be skewed to missing nonserious events, given that there’s a threshold to enter a report).

- For comparison: >8300 children age 5-11 have been hospitalized with COVID-19 in the U.S. (in total close to 1,100 pediatric COVID-19 deaths have now occurred in the U.S., and at least 52 have died of MIS-C.

- The COVID complication MIS-C is most common in this age group (median age 9): Its incidence is relatively high at 1 in 3200 SARS-CoV-2 infections – 1-2% of MIS-C patients die.

The screenshot below from the Jan 5, 2022, ACIP meeting, shows the vaccine-associated risk of myocarditis

5. A new CDC study found that the risk of new-onset diabetes was increased in children (age 18 and younger) who contracted COVID-19

This new analysis by Barrett et al. was based on two cohorts (80,893 and 430,439 patients) with COVID-19, where the children had a mean age of 12.3-12.7. Of these patients, 0.7% and 0.9%, respectively, had been hospitalized due to COVID-19.

The diabetes risk was 166% and 31% higher (in the two different cohorts) in the COVID-19 groups compared with the non-COVID-19 groups. So the risk increase was quite different between the two groups, and a smaller risk increase was noted in the larger cohort.

Compared with the risk associated with prepandemic (2017-2018) acute respiratory illnesses (ARI), COVID-19 was associated with a 116% higher risk of new-onset diabetes (95%CI 1.64–2.86). This gives an indication of the relative risk increase compared with other respiratory infections that still circulate.

The data is consistent with some prior reports for children, such as the study by Unsworth et al. The authors of the new study write, “Preventing COVID-19 among children and teens is important to slow the spread and protect them from other possible effects of the disease“

Note that the new study was not able to differentiate between type 1 and 2 diabetes, and could not account for e.g. the possible presence of obesity (other data indicates that obesity can increase the risk of having a more severe course of COVID-19 even in children). As such, it is also possible that COVID-19 hastened the onset of e.g. type 2 diabetes, due to already existing insulin resistance. In this context, they lacked information on whether the children did in fact have prediabetes. Finally, it’s possible that the non-covid comparison group included patients who had actually also had previously had covid (if so, the risk from COVID-19 would be lower).

Med vänliga hälsningar

Jonathan Cedernaes

Leg. läkare, Ph.D. och Docent i medicinsk cellbiologi